‘TOO MUCH IN THE SUN’

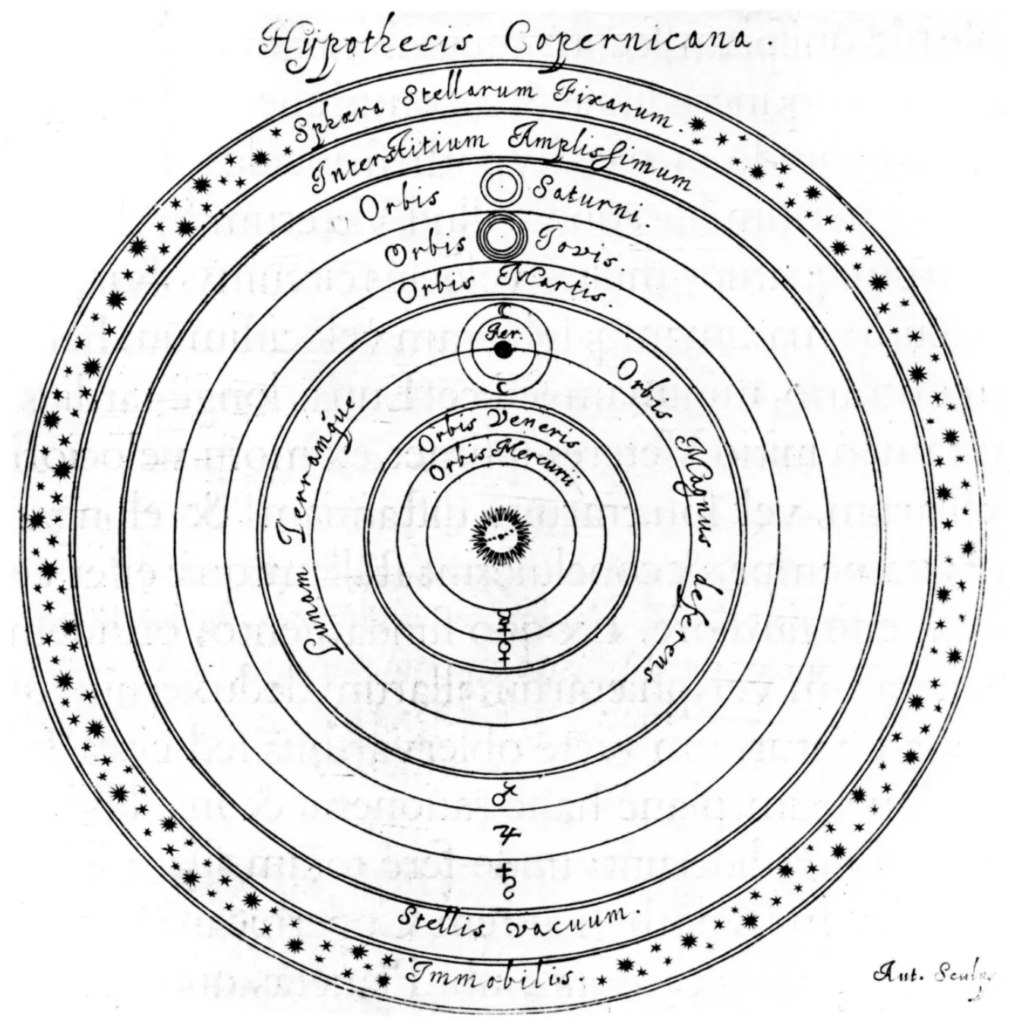

As already mentioned, it is a misconception that the heliocentric theory in itself sparked off a notorious religious fervor. Although Copernicus dedicated his book to Pope Paul III, he was not, as many assume, simply boot-licking in an attempt to head off papal disapproval. After all, Paul was quite happy with Copernicus’ theories ten years before On the Revolutions was published. In the dedication, somewhat airily, Copernicus explained his reluctance to go public by saying he wanted

to avoid harsh words from lesser scholars: he was not concerned it might stir up theological controversy, let alone accusations of heresy.

Even the notorious preface, apologetically explaining that the ideas contained therein were just theories, no more valid than any other about the workings of the heavens, was designed to placate scholars. The preface was actually written by a Lutheran theologian, Andreas Osiander, who oversaw the printing of On the Revolutions after Copernicus’ death. But because Osiander didn’t make his

authorship clear, many readers assumed the preface expressed Copernicus’ own position. Georg Rheticus, the mathematician who persuaded Copernicus to go public with his theory, later threatened

to beat Osiander up for his audacity.

The heliocentric theory raised no major theological difficulties anyway. True, there are a handful of implications in the Old Testament concerning the immobility of the world. The First Book of Chronicles, for example, states that, ‘The world is firmly established; it cannot be moved’,38 and

Joshua is said to have convinced God to stop the sun in the sky, which implies that it was the sun, not the Earth, which moves.39 But in the end few churchmen thought Copernicus’ theory was worthy of oiling the rack and heating the pincers.

Ironically, any religious objections came not from the Vatican but from Protestants, although even the most hellfire-and-damnation regarded the theory as mere folly as opposed to blasphemy. Martin Luther himself ridiculed it, but mainly because he was aghast at the suggestion that astronomy could have got it so fundamentally wrong for so long.

This was also largely the position of scholars, who too were disturbed for another reason, which is less obvious today. Proposing that traditional astronomy was profoundly flawed seemed intimidating, since it implied that human understanding of the order of the universe, and the way one part influenced another, was seriously lacking. If Copernicus was right, then everything changed.

This was not yet the era of science as we know it in the modern sense. Even learned men such as Copernicus and Johannes Kepler believed that a greater understanding of the movements of the heavenly bodies would improve the accuracy not only of astronomy but also its esoteric twin, astrology. No astronomer at that time believed the workings of the universe were due to impersonal physical forces. To them, God had decreed that the universe should operate in the way it did. As such, discovering how it worked offered an insight into the divine mind, and might also throw light on God’s plan for all creation. This mindset drove the likes of Kepler who, building on Copernicus’ work, established the laws of planetary motion.

Kepler (1571–1630) was another great name of the scientific revolution who was steeped in the Renaissance occult tradition. He believed that the planets, including the Earth, are living entities with their own world souls and that the seat of the anima mundi is in the sun. As an astrologer he wrote that a new star that appeared in 1604 portended major changes on Earth.

Unsurprisingly, his writings also reveal a detailed knowledge of the Corpus Hermeticum.

SOURCE: The Forbidden Universe, The Occult Origins of Science and the Search for the Mind of God by Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince)